Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English. The Spanish-American War took place in the late eighteen hundreds during the administration of President William McKinley. On December tenth, eighteen ninety-eight, the United States and Spain signed a treaty in Paris officially ending the war between them. However, the fighting had stopped much earlier. Spain had made the first move toward peace after its forces surrendered at Santiago, on the Cuban coast. A few weeks before that, the United States Navy had destroyed Spain's Atlantic fleet. The American naval victory ended any chance that Spain could win the war. This week in our series, Doug Johnson and Steve Ember continue the story of President William McKinley and the Spanish-American War.

Late in July, the French ambassador in Washington gave President William McKinley a message from the Spanish government. Spain asked what terms the United States would demand for peace. President McKinley sent an immediate answer. Spain, he said, must give up Cuba. It must also give to the United States the islands of Puerto Rico and Guam. And he said Spain must recognize the right of the United States to occupy Manila in the Philippines. The future of the Philippines, he said, would be decided during negotiations on a peace treaty. McKinley's terms seemed severe to Spain. But Spain had no choice. It could not continue the war. So, ten weeks after war broke out, Spain agreed to stop the fighting and accept the American terms. It signed a peace agreement in Washington on August Twelfth. A Spanish note protested sadly that the agreement took away the last memory of a glorious past. "It expels us from the western hemisphere, which became peopled and civilized through the proud efforts of our fathers."

The two countries agreed to meet in Paris to negotiate details of a peace treaty. The talks opened October first. The two sides agreed quickly on the issue of Cuban independence, and an American takeover of Puerto Rico and Guam. But they could not agree on what to do about the Philippines. At the beginning of the talks, the United States was not sure if it wanted all or only part of the Philippines. At first, President McKinley wanted Spain to give up only Luzon, the main island. Then he decided that the United States should demand all of the Philippines. McKinley explained later how he made this decision. "I thought first we would take only Manila. Then Luzon. Then other islands, perhaps. I walked the floor of the White House many nights. More than once, I went down on my knees and asked God to help me decide. "And one night," said McKinley, "It came to me this way: "That we could not give the Philippines back to Spain. That would be cowardly and dishonorable. We could not turn them over to France or Germany, our trading competitors in Asia. That would be bad business. We could not leave them to themselves.

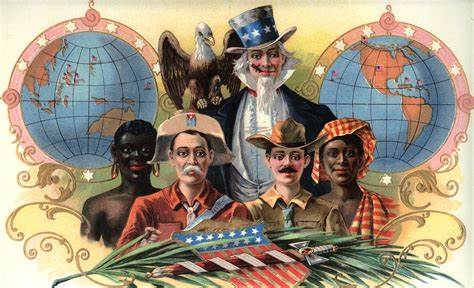

They were not ready for self-government. So, there was nothing for us to do but to take them all. And to educate the Filipinos, to civilize them, and make Christians of them. "With that decision," said McKinley, "I went to bed and slept well." Spain, however, did not want to give up the Philippines. It protested that the United States had no right to demand the Islands. True, Americans occupied Manila. But they did not control any other part of the Philippines. The two sides negotiated for days. Finally, they reached an agreement. Spain would give all of the Philippines to the United States. In return, the United States would pay Spain twenty-million dollars. With this dispute ended, the peace treaty was quickly completed and signed. But trouble developed when President McKinley sent the treaty to the United States Senate for approval. Many Americans opposed the treaty. They thought McKinley was wrong to take the Philippines. Opponents of the treaty included former President Cleveland, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, labor leader Samuel Gompers, writer Mark Twain, and others. They organized anti-imperialist groups in many cities to oppose the treaty. They made speeches and published newspapers explaining their opposition. Imperialism, they said, had ruined ancient Rome. And it would ruin the American republic.

They said colonies halfway around the world would be costly to protect. A large army and navy would be needed. They said colonial policies violated important democratic ideas upon which the United States had been built. We went to war with Spain, they said, to free Cuba from its colonial masters...not to make ourselves masters of the Philippines. Republican Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts led the Senate fight for the treaty. The opposition was led by the other Massachusetts senator, George Hoar, also a Republican. Senator Lodge appealed to national pride. He urged the Senate not to pull down the American flag. Rejection of the treaty, he said, would dishonor the president and the country. It would show that we are not ready as a nation to enter into great questions of foreign policy. Senator Albert Beveridge of Ohio also spoke in support of the treaty. Senator Beveridge said the Pacific would be of great importance in coming years. Therefore, he said, the power that rules the Pacific will be the power that rules the world. And, with the Philippines, that power is -- and forever will be – the United States.

Senator Hoar spoke strongly against the treaty. He said that taking over the Philippines would be a dangerous break with America's past. He said the greatest thing the United States had was its tradition of freedom. To take the Philippines, he said, would deny that tradition. It would violate the Constitution and the ideas contained in the Declaration of Independence: the idea that all men are created equal...and that government exists only with the permission of the governed. The Senate vote on the treaty was set for February sixth. It seemed that the opposition had enough votes to reject it. But several things happened before the vote. William Jennings Bryan, the leader of the Democratic Party, opposed the take-over of the Philippines. But he urged Democratic senators to vote for the treaty. Bryan was looking ahead to the presidential election in nineteen hundred. He believed that the Philippines' takeover would cause the United States nothing but trouble. He could put the blame for all the trouble on the Republicans. Then -- if he was elected president -- the Democrats could give the Philippines their independence. Bryan succeeded in getting seventeen Democrats and Populists in the Senate to vote for the treaty.

Two days before the vote was taken, violence broke out in the Philippines. President McKinley, without waiting for the Senate to act, ordered the American military government in Manila to extend its control throughout the Philippines. The leader of the Philippine rebels, Emilio Aquinaldo, opposed the order. Rebel forces prepared to fight. On the night of February fourth, thirty thousand rebels attacked American forces around Manila. Sixty Americans were killed, and more than two hundred seventy were wounded. Rebel losses were much higher. News of the rebel attack caused some Senators to change their minds about the Philippines. Some who had opposed the treaty now agreed with the Washington Star newspaper that "the Filipinos must be taught to obey." Eighty-four Senators were present for the vote on the treaty. To pass, the treaty needed a two-thirds majority -- fifty-six votes. One by one, the Senators voted. Then the count was announced. Fifty-seven of the lawmakers had voted yes. Only twenty-seven had voted no. The treaty was approved. The Philippines belonged to the United States.