This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Annie Sneed.

Plastic is lightweight, malleable, durable. But it has also become so widespread that it's ending up in a lot of unwanted places—including our own bodies. That's according to a new study, which found that humans are consuming a shocking amount of so-called "microplastics".

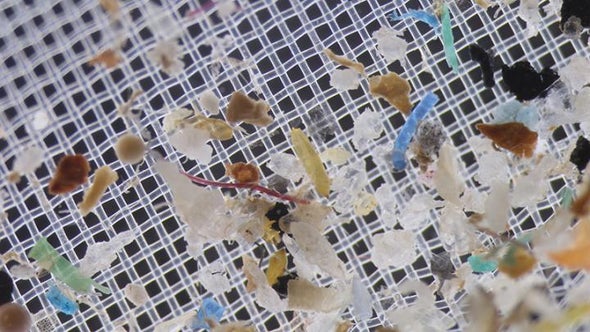

"Microplastics, the kind of current working definition, is plastic less than five millimeters. So people commonly equate that to something like a grain of rice or a sesame seed and down in terms of size class. I will say that most of the microplastics that people are interacting with are quite a bit smaller than the sesame seed size, which I think always kinds of shocks people when we start talking about the numbers because they kind of can't see a lot of these things, at least with the naked eye."

Kieran Cox, a PhD candidate in marine biology at the University of Victoria in Canada and one of the authors of the study, which is in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Microplastics come from numerous sources. They can be pieces shed from larger plastics or they may have been designed small to begin with.

For their study, Cox and his team pulled together past scientific literature that calculated the number of microplastics in things we commonly consume, such as in tap and bottled water, sugars, seafood—even in the air that we breathe. This analysis helped them figure out the baseline amount of microplastics that people are consuming every year. They couldn't include common foods like beef, poultry, vegetables and dairy in their analysis because data on them doesn't exist yet. In fact, their study could account for only 15 percent of people's caloric intake.

Even missing the majority of what people swallow, the research revealed that—at the very least—humans appear to consume somewhere between 74,000 and 121,000 microplastic particles every year. That number goes up for people drinking bottled water rather than tap water. Now, is all this plastic safe to ingest? We simply don't know yet.

"This is kind of the first estimate of dose, you could say, right? So if you're thinking in terms of toxicology and ecotoxicology, dose is a very important factor to think about, and so this kind of presents the first estimate, but it is very much an underestimate because of what we don't know."

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Annie Sneed.