This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Just like here on Earth, we have earthquakes, the planet Mars has "Mars-quakes."

"Although the quakes we see on Mars are actually more similar to the kinds of things we see in the middle of plates on the earth, what we call inter plate earthquakes. And so something that might happen in Montana or South Carolina, for example."

Bruce Banerdt, a planetary geophysicist at the Jet Propulsion Lab in California. He explains that as the hot center of the planet cools, it slowly shrinks. "So the frozen outer layers, basically, after a while, they're too big for the rest of the globe, and they have to kind of crinkle to stay, you know, contiguous on a shrinking ball." And that crinkling causes quakes.

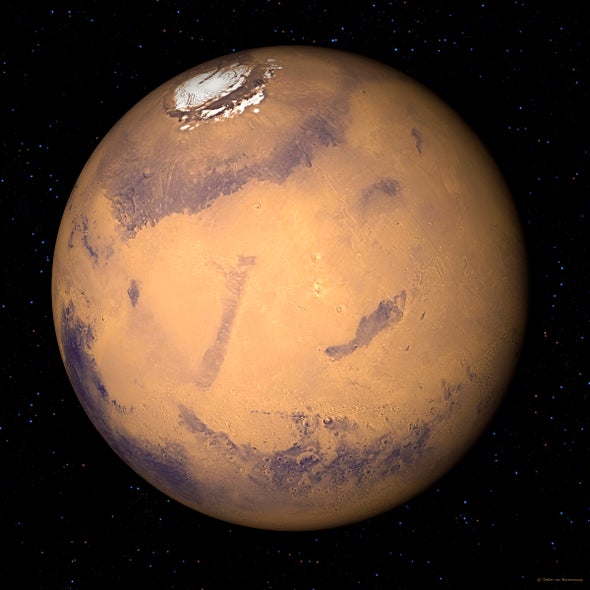

NASA's InSight mission, which landed on the Red Planet about a year ago, placed a seismometer on the planet's surface to listen for quakes. And it's captured signals from more than 100—some large enough that you'd feel them if you were standing nearby. Like this magnitude 3.7, recorded back in May.

(CLIP: Marsquake sound in)

Just to know, it's been sped up to be audible—and you really need headphones to hear the ferocious rumbling.

(CLIP: Marsquake sound out)

"We use these signals from Mars-quakes to probe the deep interior of Mars. They work almost like x-rays, you know. They pass through the planet; they bounce off boundaries, like between the crust and the mantle, the way an x-ray bounces off a bone. And we can actually, over time, put together a 3-D image of the inside of a planet, using seismology."

To accurately read those seismic sounds, though, the researchers have to filter out background noise—such as these "dinks and donks", as they call them:

(CLIP: Dinks and donks sample)

The scientists think those sounds might simply be the seismometer creaking as it expands and contracts with daily temperature swings.

InSight also has another tool, a heat probe, to directly measure the heat seeping out of that slowly cooling core. It's nicknamed "the Mole," because it's designed to burrow 16 feet below the Martian surface—although, right now, it's stuck at just 14 inches deep.

If the geophysicists can get the Mole to burrow better, it'll give scientists one more tool to understand the Red Planet's deep history—maybe even including how Mars and the Earth formed, 4.5 billion years ago—in what must have been a truly Richter-breaking shake-up.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.