This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Sunday morning, September 28th, 1969, a fireball lit up the skies north of Melbourne, Australia.

"People were getting ready to go to church, and then they heard this loud sonic boom. Some of them saw the bright fireball in broad daylight, and people were surprised. They said, 'What's going on, especially those who were not outside, they really...is there an airplane that came down? It sounded really dramatic.' And then suddenly, shortly after that, there was a smell that was detectable over the whole area. People describe it as methylated spirits—a strong organic smell."

Cosmochemist Philipp Heck of Chicago's Field Museum describing the spectacular arrival of what's now known as the Murchison meteorite, named for the village where it was found. A portion of the space debris now resides at the Field Museum. And Heck says it's our best source of presolar stardust—meaning stardust older than the solar system and the sun itself.

"I call it a scientific treasure trove."

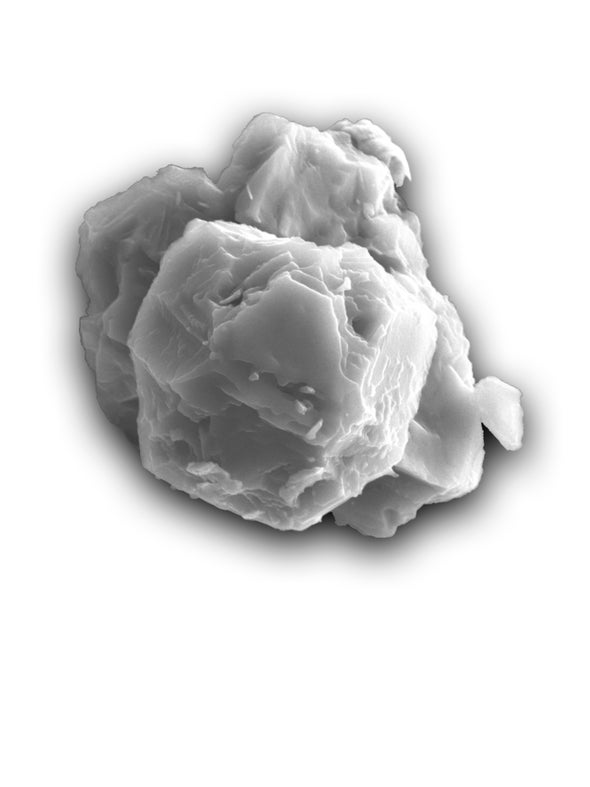

Inside the meteorite is dusty debris left over from when stars slightly larger than our sun fizzled out. Over millions of years, those dust grains were battered by cosmic rays, which slightly altered their composition. Atoms of elements got broken down into smaller ones like neon and helium. And then some of that stardust was swallowed up within rocks—such as the Murchison meteorite—during the formation of our solar system. Those rocks served as time capsules, preserving the material for unimaginable ages.

Previous astronomical observations have hypothesized that there was a "baby boom" of stars about seven billion years ago. By studying the Murchison grains' elemental composition, Heck's team was able to date 49 grains and found that two thirds of them were 4.6 to 4.9 billion years old.

"And that all makes sense, because the parent stars—they formed seven billion years ago, and it took them about two to 2.5 billion years to evolve, become planetary nebula and become dust-producing."

The results are in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Some of the grains are actually up to seven billion years old, making them the most ancient material on Earth—delivered here without notice, on a quiet Sunday morning, 50 years ago.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.