This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Annie Sneed.

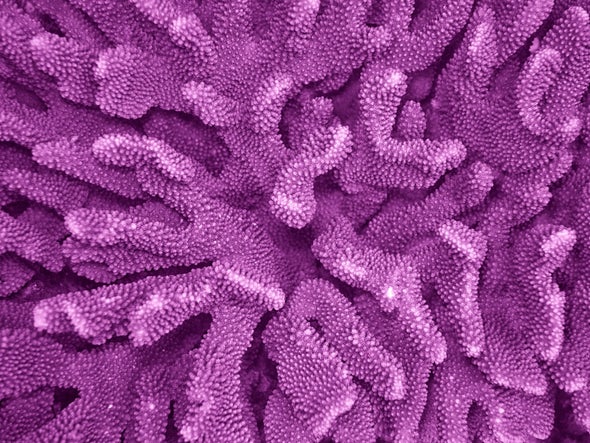

Coral reefs are among the most productive ecosystems in the world. They're also in serious danger—climate change and other threats are killing them off. But researchers have come up with an invention they think could help the reefs: 3-D-printed corals.

At the heart of reef ecosystems lies a symbiosis between corals and algae.

"Corals use light, they're photosynthesizing, so they have microscopic algae inside their tissues. And these use light to generate energy, and that energy is then transferred to the coral animal host. And that animal host, in return, transfers certain by-products to the algae, so they have a symbiosis going on."

Daniel Wangpraseurt, a coral reef scientist at the University of Cambridge.

This tight-knit bond between algae and corals is what makes reefs so incredibly productive. And because of this symbiosis, corals have evolved sophisticated skeletal and tissue structures for collecting sunlight.

"So usually, you would have this rapid light attenuation. But through the skeleton, light is pumped and guided into deeper, otherwise shaded areas. So there's a lot of tricks that corals use. And in our work, we copied some of them."

Wangpraseurt and his colleagues imaged corals to analyze their skeletal and tissue makeup. They then used a 3-D bioprinter to build an intricate structure that mimics real corals. The printed corals were made of biomaterials like cellulose and had algae embedded in them. And because the researchers were able replicate coral structure so well, the algae grew tremendously—up to 100 times more densely than they normally grow in the lab.

Wangpraseurt says their 3-D-printed creation could be used as a medium to grow algae to produce bioenergy and also as a tool for studying the coral-algae symbiosis.

"At the same time, of course, there are many other ways this technology can be further scaled and improved to create something like artificial corals in the future. So this is just the first step, where we created the animal host, but we're now continuing to further replicate this animal-algal symbiosis. And we're developing model systems. And eventually, of course, it would be nice that this can have direct applications in coral reef restoration."

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Annie Sneed.