德国幽默

Get thee to an Institute

闻所未闻的幽默培训

Germans concede that in humour they need professional help

德国人认为幽默需要专门的训练

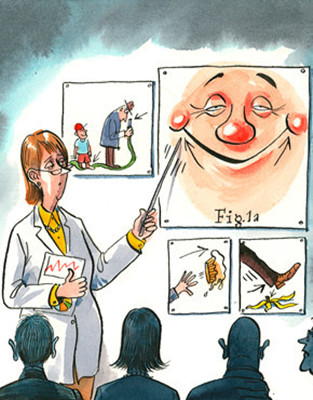

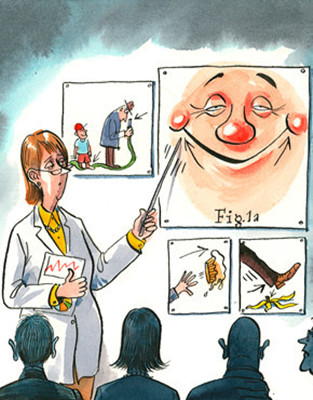

EVA ULLMANN took her master's degree in 2002 on the part that humour has to play in psychotherapy, and became hooked on the subject. In 2005 she founded the German Institute for Humour in Leipzig. It is dedicated to “the combination of seriousness and humour”. She offers lectures, seminars and personal coaching to managers, from small firms to such corporate giants as Deutsche Bank and Telekom. Her latest project is to help train medical students and doctors.

2002年,伊娃·乌尔曼以“幽默在心理治疗中的作用”为论文研究主题获得了博士学位,并对该主题产生了巨大的兴趣。2005年,她在莱比锡城创建了德国幽默研究所,致力于研究“严肃和幽默之间的关系”。伊娃为管理者们(从小公司到诸如德意志银行和德国电信之类的商业巨头)都有进行演讲、开展讨论会和个人辅导。最近,她正在着手训练医学学生和医生。

There is nothing peculiarly German about humour training. It was John Morreall, an American, who showed that humour is a market segment in the ever-expanding American genre of self-help. In the past two decades, humour has gone global. An International Humour Congress was held in Amsterdam in 2000. And yet Germans know that the rest of the world considers them to be at a particular disadvantage.

奇怪的是,德国并没有特定的幽默培训。一个叫约翰·莫瑞尔的美国人指出曾经一度膨胀的资历的美国精神中,幽默也是市场的一部分。过去的20年里,幽默走向了国际。2000年国际幽默大会在阿姆斯特丹建立。在此之前,德国人还不知道在其他国家的人眼里,他们十分严肃。

The issue is not comedy, of which Germany has plenty. The late Vicco von Bülow, alias Loriot, delighted the elite with his mockery of German pretension and stiffness. Rhenish, Swabian and other regional flavours thrive—Gerhard Polt, a Bavarian curmudgeon, now 72, is a Shakespeare among them. There is lowbrow talent too, including Otto Waalkes, a Frisian buffoon. Most of this, however, is as foreigners always suspected: more embarrassing than funny.

这个议题并非是个喜剧,德国的此类例子很丰富。已故的 Vicco von Bülow, 别名Loriot,曾就以讽刺德国人的自负和固执娱乐精英。莱茵河人,斯瓦比亚人和其他地区的精英们层出不穷——Gerhard Polt是个巴伐利亚人,脾气很怪,现年72岁,就是其中的一个莎士比亚。也有一些比较肤浅的人物,比如弗里斯兰小丑Otto Waalkes。然而大多数情况下,外国人的怀疑:往往是尴尬大于有趣。

Germans can often be observed laughing, uproariously. And they try hard. “They cannot produce good humour, but they can consume it,” says James Parsons, an Englishman teaching business English in Leipzig. He once rented a theatre and got students, including Mrs Ullmann, to act out Monty Python skits, which they did with enthusiasm. The trouble, he says, is that whereas the English wait deadpan for the penny to drop, Germans invariably explain their punchline.

人们常常可以看到德国人大笑。他们真的在很努力地发出笑声。在莱比锡大学教授商务的英国人詹姆斯·帕森斯说,“他们没法变的幽默,但他们可以表现得很幽默。”他曾经租了一个歌剧厅,邀请了一些学生,包括乌尔曼一起表演Monty Python短剧。他们表演得很有热情。但是,问题是,英国人会面无表情地等硬币落下来而德国人则认为很有笑点。

At a deeper level, the problem has nothing do with jokes. What is missing is the trifecta of irony, overstatement and understatement in workaday conversations. Expats in Germany share soul-crushing stories of attempting a non-literal turn of phrase, to evoke a horrified expression in their German interlocutors and a detailed explanation of the literal meaning, followed by a retreat into awkward politeness.

更深层次上来说,这个问题与笑话无关。他们在正常的工作交流中,没有一连串的讽刺,大话和保守言论。德国的外国移民设法通过非文学的方式,与当地人交流窝心的故事,对他们的德语朋友产生恐惧的印象并不得不解释这些词语的文学一次,因而最后会陷入尴尬的礼貌却又疏离的境地。

Irony is not on the curriculum in Mrs Ullmann's classes. Instead she focuses mostly on the basics of humorous spontaneity and surprise. Demand is strong, she says. It is a typical German answer to a shortcoming: work harder at it.

讽刺不属于乌尔曼的授课内容。相反,她主要集中在自发幽默和惊喜的基本原则。她说人们对幽默的需求很强。这是典型的德国人对待缺点的方式:埋头苦干。译者:毛慧 校对:王红兵