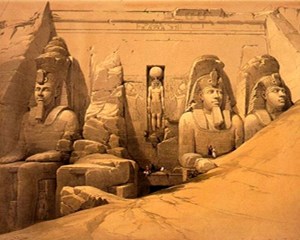

At this long distance from the coast of the Mediterranean he arrives at Ipsambul, or Abou-Simbel. Here, on the confines of the pathless and unpeopled desert, stands one of Egypt's most striking marvels—the Temple of the Sun, built by Ramesese, whose gigantic statue sits there in the solitude, still unbroken, and revealed from head to foot. This statue is repeated four times: two are buried in the sand, and the third is overthrown and in fragments; but from the fourth still looks down the face of the greatest man of the old world, who flourished long before the rise of Greece and Rome—the first conqueror recorded in history—the glory of Egypt, the terror of Asia—the second founder of Thebes, which must have been to the world then what Rome was in the days of her empire.

"The chief thought," says Dean Stanley, "that strikes one at Ipsambul, and elsewhere, is the rapidity of transition in Egyptian worship from the sublime to the ridiculous. The gods alternate between the majesty of antediluvian angels and the grotesqueness of pre-Adamite monsters. By what strange contradiction could the same sculptors and worshippers have conceived the grave and awful forms of Ammon? and Osiris? and the ludicrous images of gods in all shapes 'in the heavens and in the earth, and in the waters under the earth,' with heads of hawk, and crocodile, and jackal, and ape? What must have been the mind and muscle of a nation who could worship, as at Thebes, in the assemblage of hundreds of colossal Pashts—the sacred cats?"