This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Julia Rosen.

In the last few decades, astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets orbiting other stars. Now, scientists want to know what they look like. Do they have oceans? Atmospheres? Researchers have even searched for signs of plant life and the glow of alien city lights—although they haven't found any yet.

"We've moved on from being excited about finding exoplanets to now having to get our kicks out of characterizing them."

Moiya McTier, a graduate student at Columbia University and the host of the podcast So You Think You Can Science.

Last year, McTier's advisor challenged her to find something else on exoplanets: evidence of extraterrestrial mountains. Because mountains could offer clues about what's going on inside these planets.

"The way that those form is through the collision of tectonic plates or through lava building up in the same place over millions of years. And so that's one of the most exciting things, in my opinion, that can come out of this project, is actually being able to figure out what's underneath the surface of an exoplanet."

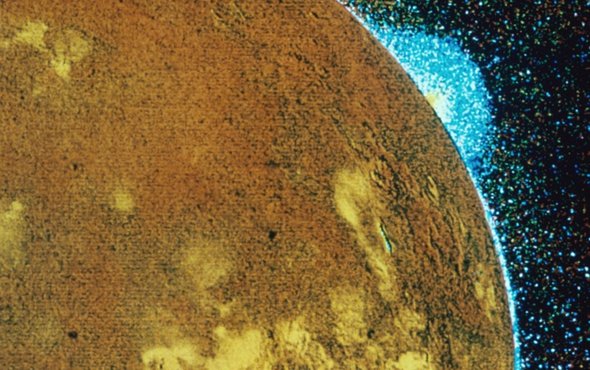

The trick was how to do it. Modern telescopes are powerful, but they can't capture pictures of exoplanets. Instead, a common way astronomers detect them is by watching as they pass in front of their star, blotting out some of the light. McTier riffed on this idea to find a way to look for mountains.

"And so, what we are doing with this mountains project is saying, okay, if a planet has a mountain on it and if that planet is rotating, then the mountain will show up in silhouette. And the silhouette will change, because the planet's rotating. So, we can study that changing silhouette—that changing shadow—to get an idea of what the surface of the planet looks like."

McTier tested the technique by modeling how the rocky planets of our solar system would look through modern telescopes like the James Webb if they were far away.

"And we were pretty heartbroken when found out that it wouldn't be possible."

But McTier calculated that it might be doable with something like the Extremely Large Telescope, which is currently under construction in Chile. Even this telescope probably wouldn't be able to measure the topography of a Mars-like body if it orbited a large star like our Sun. But if that planet circled a smaller star, like a white dwarf, it would block out enough light to be detectible. The research is in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

So, one day soon we may be able to confirm the existence of exoplanetary mountains. And with even better telescopes, maybe molehills. Or even moles.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Julia Rosen.