This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Susanne Bard.

Thousands of years ago, in what's now the Kimberley region of Western Australia, Aboriginal artists created elaborate rock paintings. Much of the artwork still exists today.

"If you're walking beside the rivers and creeks and go up into the escarpments, into rock shelters, there are just thousands of rock art sites."

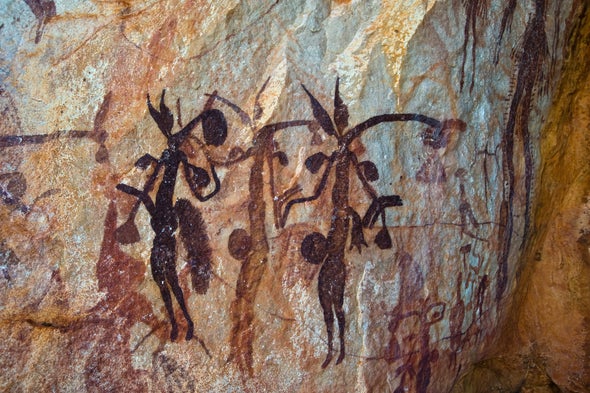

University of Melbourne geochronologist Damien Finch. The oldest paintings depict plants and animals. But later works show human figures in ceremonial attire and ornate headdresses.

"And then, around the arms and the elbows and the knees, there's decorations. And sometimes they'll be holding a clutch of boomerangs. And very often, they're very finely executed, using quite long and elegant-looking brushstrokes."

The human-centered paintings represent what's known as the Gwion style. How old the artwork is has remained a mystery, however. That's because the typical method for estimating the age of ancient objects—radiocarbon dating—relies on the presence of organic carbon. But the artists used ocher pigments that had no organic carbon.

"There is nothing organic that we can apply carbon dating to. So the only thing that we can do is look for stuff that's either been constructed on top of or underneath the paintings."

That's where mud wasps come in. The insects often incorporated organic matter into their nests, which they built on the same rock faces where artists painted. The artists would sometimes paint right on top of old nests. Finch and his colleagues were thus able to date the artwork by sampling the remains of those nests.

"If it was over the top of the painting, that tells us that the painting has to be older than that nest. But if the nest was underneath paint, the painting must be younger than the age that we determined for that nest. And in that way, we can help to build up an idea of when these paintings were created."

The analysis revealed that most of the Gwion style paintings sampled were about 12,000 years old.

"So now we can place that in the context of all the other archaeological and environmental information that we've got for the Kimberley region at that time."

The study is in the journal Science Advances.

The results provide support for the hypothesis that Aboriginal artists may have switched from painting plants and animals to depicting humans in ceremonial dress around 12,000 years ago in response to the ecological changes and rapidly rising sea levels as the last ice age ended.

Finch is now working out the age of other styles of Aboriginal rock art—with a little help from materials that ancient insects once called home.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Susanne Bard.