This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Christopher Intagliata.

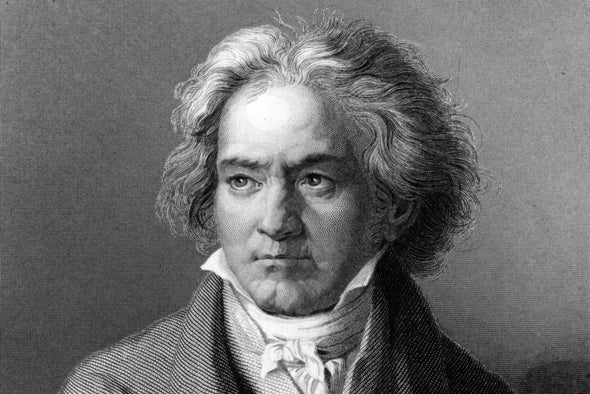

Beethoven is a giant of classical music. And the most influential, too—at least, when it comes to piano compositions. That's according to a study in the journal EPJ Data Science.

If you're wondering how data analysis could determine something as intangible as cultural influence, it's worth remembering this:

"The great thing about music: it's the most mathematical of the art forms we actually can deal with. Because a lot of it is symbolic; it's temporal. So we have symbols. The music is written in symbols that are connected in time."

Juyong Park is a theoretical physicist by training and associate professor of culture technology at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

Park and his colleagues collected 900 piano compositions by 19 composers spanning the Baroque, Classical and Romantic periods, from 1700 to 1910.

(CLIP: Musical montage)

Then they used that mathematical quality to their advantage by dividing each composition into what they called "code words," a group of simultaneously played notes—in other words, a chord.

(CLIP: Code word sample)

They then compared each chord to the chord or note that came after it...

(CLIP: Code word transition sample)

...which allowed them to determine how creative composers were at coming up with novel transitions.

The composer with top marks for novelty? Rachmaninoff.

(CLIP: Rachmaninoff sample)

But when the researchers looked at those chord transitions across all 19 composers, it was Beethoven who was most heavily borrowed from—meaning, at least among the composers in this analysis, his influence loomed the largest.

Their study comes with a couple caveats. Again, the researchers only considered piano compositions in this work—not orchestral works. And by only studying chord transitions, their conclusions wouldn't capture artists who were influential in other ways.

"It's well understood that Mozart's contribution to music comes from the musical forms that he devised. That was not very well captured by our mathematical modeling."

As for Park, the results convinced him he has some listening to do.

"Of course I do. I like Rachmaninoff's music but I have to confess, I have listened to Beethoven way more than Rachmaninoff. So after this work came out, I ended up buying his whole complete collection from Amazon, I'm waiting for this collection to arrive."

Seems that Park turned a minor interest into a major commitment—in a key way.

(CLIP: Rachmaninoff sample)

For Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.