- VOA名师答 44分钟前last Tuesday是“上周二”还是“上一个周二”?

- 立体语音 1小时前第628期:My ear itches我的耳朵很痒

- Albert 1小时前第201期:《梦华录》海外热播,国外网友花式赞美,这波文

- 英文小酒馆 1小时前第352期:镜头下,是残酷与美丽并存的真实世界。

- Gabby英 1小时前Gabby英语早读——快速

- 瞬间秒杀听力 1小时前第857期:Homesick 思乡

- 跟艾米莉一起 1小时前第949期:“炒鱿鱼”别老说“You're fi

- 愉悦口语 1小时前第1101期:go out with是和某人出去?

- 早安英文 1小时前第1203期:shanghai 不是上海?这个词的真实意

- 经济新闻 3小时前通货膨胀促使美国千禧一代百万富翁推迟购房购车

- 大千世界 3小时前网友馋哭了!外国小姐姐挑战在中国一天只吃饺子

- 新增节目

- 最近更新

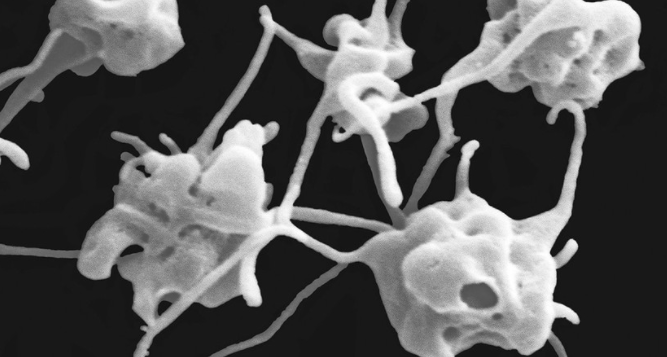

- 5小时前川大教授开发血小板膜涂层避免了支架排异(上)

- 1天前英国火车司机罢工--铁路网瘫痪5天

- 2天前前游击队员当选哥伦比亚总统

- 3天前重塑亚的斯亚贝巴(下)

- 4天前重塑亚的斯亚贝巴(上)

- 5天前欧洲央行开始进行债券利差管理

- 6天前学打鼓对自闭症孩子有帮助

- 7天前南京古生物所发现1.8亿年前蜉蝣化石

- 8天前金融市场被迫消化美联储量化紧缩计划

- 9天前美国敦促北约各国加快向乌克兰运送武器

- 最近更新

- 最近更新

- 1天前阿富汗遭遇20年"最致命"地

- 2天前亚马逊将在美国启用无人机送货

- 3天前特斯拉辅助驾驶事故占全美七成

- 4天前人生苦短, 我们要少"生气"

- 5天前如何防治害虫

- 5天前美国堕胎率上升

- 6天前美国黄石国家公园因洪水关闭

- 7天前尼泊尔首都垃圾成山

- 8天前专家称干旱或将成为智利的常态

- 9天前尼日利亚森林正加速消失

- 影视·英语 进入频道>>

- 06-01温馨电影《千与千寻》第14期:白龙还活着?(en

- 05-31温馨电影《千与千寻》第13期:送回人类世界

- 05-30温馨电影《千与千寻》第12期:我们还会再见吗?

- 05-29温馨电影《千与千寻》第11期:婆婆会杀了你的

- 05-28温馨电影《千与千寻》第10期:不吃东西会消失的

- 05-27温馨电影《千与千寻》第9期:有入侵者

- 06-24听歌学英语:是你呀It's You

- 06-23听歌学英语:快没电1%

- 06-22听歌学英语:跟你困在一起Stuck With You

- 06-21听歌学英语:洛杉矶女孩LA Girls

- 06-20听歌学英语:做你的唯一Be The One

- 06-19听歌学英语:(满屏日漫风)钻石城之光Diamond

- 06-18听歌学英语:(乖乖女黑化)我的天My Oh My

- 06-17听歌学英语:(很棒的鼓点)像那样Like That

- 06-16听歌学英语:(异地恋)慢下来Slow Down

- 06-15听歌学英语:(经典老歌)Y.M.C.A

- 06-14听歌学英语:朋友Friends

- 06-13听歌学英语:热浪Heat Waves

- 最近更新

- 10-232019年12月英语六级考试真题试卷附答案(完整

- 10-232019年12月英语六级考试真题试卷附答案(完整

- 10-212019年12月英语六级考试真题试卷附答案(完整

- 10-212019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第3套

- 10-212019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第3套

- 10-192019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第3套

- 10-192019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第2套

- 10-192019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第2套

- 10-162019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第2套

- 10-152019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第1套

- 10-152019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第1套

- 10-152019年12月英语六级阅读真题及答案 第1套

- 02-252021年英语专业四级听力真题 对话2

- 02-252021年英语专业四级听力真题 对话1

- 02-252021年英语专业四级听力真题 演讲

- 02-252021年英语专业四级听力真题 听写

- 06-01专四英语作文高分范文背诵(MP3+中英字幕)第6

- 05-31专四英语作文高分范文背诵(MP3+中英字幕)第6

- 06-27诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《玉京秋·自题〈种瓜小影〉》译

- 06-27王毅在二十国集团阿富汗问题领导人特别峰会上的讲话

- 06-24诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《孤鸾·病中》译文

- 06-24戴维·马尔帕斯在世界银行2021年年会开幕记者会

- 06-23诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《惜黄花慢·孤雁》译文

- 06-23王毅在纪念不结盟运动成立60周年高级别会议上的讲

- 06-22王毅在亚信第六次外长会议的讲话(中英对照)

- 06-22诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《摸鱼儿·谢邻女韩西馈食》译文

- 06-21乐玉成接受中国国际电视台专访(2)(中英对照)

- 06-21诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《春从天上来·梅花》译文

- 06-20诗歌翻译:贺双卿-《春从天上来·饷耕》译文

- 06-20乐玉成接受中国国际电视台专访(1)(中英对照)

- 07-14商务英语活学活用 名片(4)

- 07-13商务英语活学活用 名片(3)

- 07-12商务英语活学活用 名片(2)

- 07-11商务英语活学活用 名片(1)

- 07-08商务英语活学活用 商务礼节(4)

- 07-07商务英语活学活用 商务礼节(3)

- 07-06商务英语活学活用 商务礼节(2)

- 07-05商务英语活学活用 商务礼节(1)

- 07-01商务英语活学活用 办公室里的咖啡和点心(4)

- 06-30商务英语活学活用 办公室里的咖啡和点心(3)

- 06-29商务英语活学活用 办公室里的咖啡和点心(2)

- 06-28商务英语活学活用 办公室里的咖啡和点心(1)

- 06-232014年9月北京市全国英语等级考试报名时间

- 08-23培养公共英语学习中的良好习惯

- 07-26江苏淮安2013年职称英语考试证书领取通知!

- 07-26湖北襄阳2013年职称英语考试证书领取通知!

- 07-169岁女孩10岁男孩口语满分过公共英语四级考试

- 07-16全国公共英语:等级考试技巧心得

- 07-16六招迎战PETS考试

- 07-16吉林2013年下半年公共英语等级考试费用

- 07-16安徽2013年下半年全国英语等级考试报名时间

- 07-12公共英语三级考试:完形填空题型不容忽视

- 07-12公共英语考试高分经验

- 07-12公共英语考试中所有英语介词的翻译技巧

- 07-02新东方GRE核心词汇考法精析 List31:Un

- 06-22GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-21GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-20GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-19GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-18GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-17GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-16GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-15GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-14GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-13GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-12GRE数值比较(官方题库Barron)每日一题

- 06-03雅思听力地名常见拼写错误

- 04-22雅思阅读填空题解题技巧归纳

- 04-16雅思听力标准—六大基本功

- 04-15三步走攻破雅思听力真题中的学术讨论题

- 04-092019雅思听力是不是变得更难了?

- 04-08雅思听力训练同义替换总结有多重要

- 04-052019雅思听力考试备考方向指导

- 04-04雅思听力复习方法:模拟训练

- 03-26雅思听力技巧"抢分"从这三方面入手

- 03-25雅思听力如何巧做选择题

- 03-19直击要害的雅思听力备考三大法则

- 03-18雅思写作模板之保护野生动物

- 12-08第59课 商务英文邮件之邮件咨询

- 12-07第58课 商务英文邮件申明需求

- 12-06第57课 商务英文邮件九大原则2

- 12-05第56课 商务英文邮件九大原则1

- 12-04第55课 英语电话之留存对方联系方式

- 12-01第54课 英语电话之给某人留电话

- 11-30第53课 英语电话之表达信号不好

- 11-29第52课 英语电话之交代来电事由

- 11-28第51课 英语电话之礼貌要求对方

- 11-27第50课 英语电话之向对方承诺传达到位

- 11-24第49课 英语电话之对方不方便应对

- 11-23第48课 英语电话之不方便接电话